Mineappolis writer Abra Staffin-Wiebe brings us a new take on an old Russian fairy tale: the quest for a blessing from the elusive firebird. In this iteration, young Ekaterina celebrates her fourteenth birthday, and a rare firebird sighting sets in motion a chain of events that will change her life forever.

This short story was acquired and edited for Tor.com by editor Liz Gorinsky.

Ekaterina couldn’t bear to go to sleep and miss the last moments of what had been a wondrous fourteenth birthday. She sat on the window seat in her bedroom and hugged her knees as the last minutes of the day melted away like spring snow. In the corner of the room, her maid Agafya snored softly.

Below them, the parlor clock began its midnight toll. Agafya startled awake with the first peal of the bell.

“Ekaterina—?” she mumbled blearily. Her eyes sharpened. “Why are you still awake? Have you taken your draught?”

“Must I? It’s my birthday,” Ekaterina protested.

The clock continued to chime. Agafya paled. “What time is it?”

“Midnight, I think.”

Agafya sprang up and flew across the room to seize the goblet waiting beside Ekaterina’s bed. “You must!”

“Oh, very well,” Ekaterina grumbled. She took the cup and raised it to her lips. The clock finished tolling twelve as the last drops slid down her throat.

Agafya sighed, her shoulders untensing as she took the empty cup from Ekaterina’s hand. “Why are you still awake, child? You should be tired after such a long day. And what a feast it was! So many guests came to see my little bird gloriously launched into the world! Even Councillor Nikitin said what a fine affair it was, and he has seen the splendors of the Tsar’s court.”

“Oh, it was wonderful, Agafya! Nothing so interesting will happen to me again for years!”

Agafya sniffed. “Be patient. Ordinary joys and sorrows will seem interesting enough, I promise you.”

“I suppose.” Ekaterina’s cheeks warmed. “Nikolai Semyonevich Egorov was very attentive. So handsome, too. And the Egorovs have lived near us for centuries, and—”

“Do not pin your heart to an Egorov,” Agafya interrupted.

“What? Why not?”

“That story is not mine to tell. You must ask your papa later. Now, it is well past the proper bedtime for young ladies, even young ladies of the great and advanced age of fourteen.”

“Yes, Agafya. I’ll go to sleep soon, I promise.”

“See that you do.” Agafya yawned, retired to her cot, and was soon snoring away.

Ekaterina returned to gazing out into the night, remembering the compliments that Nikolai had whispered to her before Agafya the ever-vigilant had interrupted their conversation.

Perhaps Agafya was making an elephant out of a fly? Ekaterina’s papa had invited Nikolai. Would he have done that if things were so ill between their families? Agafya was often overprotective, shooing Ekaterina away from boys and even interrupting visits with other young ladies if the conversation strayed to topics she deemed not quite proper.

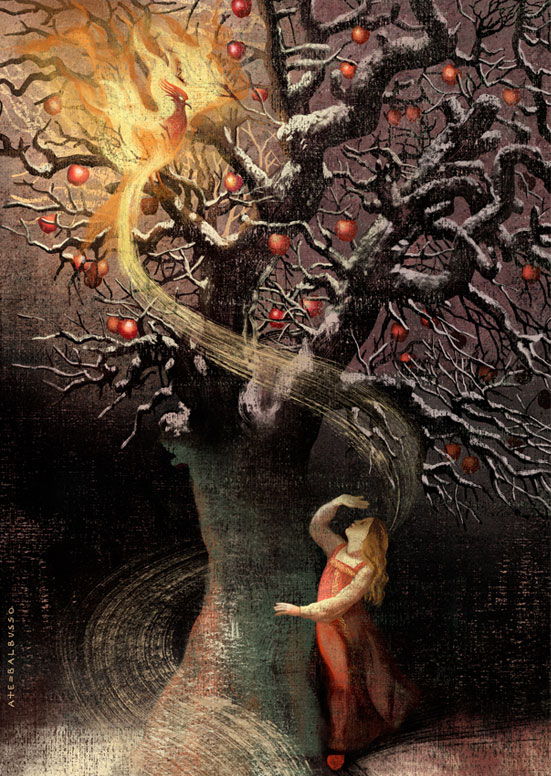

Ekaterina hugged her knees even tighter and glanced out at her father’s apple orchard. She gasped as she saw fire leaping between the branches of the frontmost apple trees.

Ekaterina jumped to her feet to shout “Fire!” Her cry died of sheer astonishment in the next second, when the fire . . . flew.

Her eyes widened. Even as a little girl, when her baba told her stories of the Firebird, Ekaterina had never imagined that she might someday see it herself. The good fortune brought by the touch of its shadow could make this the most important birthday of her life. If she hurried, she might reach the Firebird before it vanished.

She had no time to don proper attire. She seized the everyday sarafan that Agafya had worn earlier in the day and pulled it on over her light nightgown. Dress on, she stopped only to push her feet into the embroidered slippers beside her bed. She eased the door open slowly so as not to wake Agafya, and then she was off.

Downstairs, she swung her fur cloak around her shoulders, pushed the door open, and ran lightly out over the first snow. The guard dogs yipped inquisitively as she ran past.

Ekaterina’s parents always scolded her for running—such an unladylike exertion—but she was an excellent runner. She could outrace all six of her older brothers, though they teased her that it was because of her large feet. Now she sprinted as fast as she could. The light blanket of snow muffled the snap and crack of twigs as she ran. Melting snow soaked her thin slippers, and the jagged ends of fallen twigs poked her feet.

Only a thin sickle moon hung in the sky, but the apple orchard was lit as if by a golden harvest moon. Ahead of her, dancing fire flitted through the trees, illuminating the last hanging remnants of the apple harvest.

She chased the Firebird through her father’s orchard and across the bordering farmland. She had to slow down, or she would have turned her ankle as she ran over uneven fields of harvested rye, but cutting through the fields would get her there faster than taking the curving road.

The flickering flame vanished just before. Ekaterina stumbled to a halt in front of the village. Inside the homes, hearth fires would be banked for the night, as peasants huddled together under quilts to stay warm. Outside, picketed goats clustered close to each other for heat. She searched for any hint of light. Then the fire appeared again, rooftop-high, as the bird dodged between houses and out the other side of the village. Ekaterina broke back into a run.

At the edge of the village, she hesitated. Cold seeped through her fur cloak and froze perspiration to her body. Snow soaked her slippers and turned her feet to blocks of ice. In front of her lay Chyorniy Forest. Children weren’t allowed to play near its edge, and even the women who picked mushrooms in the forest kept within sight of the village and stayed in groups.

The Firebird’s wings flickered through the forest in front of Ekatarina. She thought of her family, gathered her bravery, and plunged into the darkness. The thin moon’s light was too puny to illuminate the forest, and the deeper she went, the darker it became. She slowed to a walk, her hands in front of her to keep from running into a tree. The flickers of fire grew farther and farther away, and the forest grew darker and darker around her, until she knew she must be lost. She began to shiver and think about the stories her baba had told her of what happened to little girls who wandered into Chyorniy Forest.

She needed to figure out which way her home was. She could see nothing where she stood, so she felt around until she found a tree trunk so wide that her arms could not span it. With such a wide trunk, it must be a giant grandpapa of a tree.

Darkness spread itself around her. She could not tell tree branches from the night sky. She could not even see her own hands gripping the tree. Sometimes she thought she could see patches of lighter darkness where her hands ought to be; other times she was convinced that any difference was her imagination.

She climbed until the tree trunk split into branches with a girth no wider than her own. Then she strained her eyes looking for the glimmer of snow-covered fields in the moonlight, or the glow of a lamp in a village window. She saw nothing.

She stared up at the slim crescent moon. “God our Father,” she prayed, “rescue me, for I am lost and do not know my way.” Tears welled up in her eyes and she tried to blink them away.

When she could see again, she thought at first that the moon had grown brighter. Then the glow above her split, and the Firebird dove down toward her. Its light showed her that she sat in a towering wild apple tree. To her dazzled eyes, the tree branches appeared to be rimmed in fire.

The Firebird settled onto a branch just out of her reach and cocked its head to consider a wizened, twisted apple hanging nearby. Ekaterina smelled smoke, but although the Firebird’s feathers were made of flame, the tree did not burn. Heat caressed her face like the summer sun.

The Firebird’s shadow fell over the branches only a couple of feet away from Ekaterina. She shifted her weight and slowly inched towards the shadow and its promise of good fortune.

The Firebird’s head snapped around, and it pinned her with its diamond-edged gaze. It fanned its wings at her. Furnace heat rolled over her, and she shielded her face with her arm. When she dared look again, the Firebird had retreated well away from any branches she could reach.

The Firebird swiveled its head as it studied the barren branches around it. When she saw it hunch as if it were about to spring into the air, Ekaterina cried, “Wait!” She plucked an apple near her and tossed it toward the Firebird.

It speared the fruit with its beak, then pinned it with a foot and pecked at it.

“Come back with me,” Ekaterina said. “Even the worst apple left in my family’s orchards will taste better than a wild one. We have more than what you saw tonight! Only one of our orchards is here; the other one is at our distillery. Our trees produce only the sweetest apples. I can show you where all the best ones are.”

The Firebird’s faceted crystal eyes gleamed with reflected light. “But we are in a wild forest,” it said, “and your apple trees could not survive here. This tree is strong and right for where it is. It does not try to be an orchard apple tree. It knows what it is—and its fruit is more delicious for it. Have you even tasted it?”

To be polite, Ekaterina plucked a nearby apple and dubiously took a bite. The overwhelming sourness of it puckered her mouth. She was about to spit it out when its honey-sweet aftertaste rolled across her tongue. She chewed, swallowed, and thought for a few moments. “I like the apples my father makes brandy from better.”

“It is always better to know than to assume.”

“I don’t know where I am,” Ekaterina tried, hopefully.

“There is much you don’t know, little apple-eater,” the Firebird told her. “But you will find out.” Its wings snapped open.

She fell back and shielded her eyes from the curtain of fire. “No, wait!” she cried, but the Firebird leaped up from the tree branch and took to the sky, a comet in reverse. Nearby, a wolf howled its appreciation.

The chorus of spine-tingling wolf calls that answered made Ekaterina grip the tree trunk tightly. One of the howls sounded as if it came from directly below her.

Feeling around the tree branches and trying to remember what she’d seen in the Firebird’s light, she found her way to a natural cradle formed from three branches forking off the main trunk. She settled into that cradle, letting her legs dangle to either side of the trunk. A slight breeze on her bare ankles startled her, as she imagined a slavering wolf leaping to sink his fangs into her flesh and pull her down. Had she climbed high enough to be safe? She was certain she would not sleep a wink.

A cascade of birdsong woke her the next morning. She expected to see the Firebird, but instead a shchegol flirted its golden feathers at her as it warbled from a branch above her head.

“Oh! Dobraye utro, little one!” she greeted it.

She looked down and quickly shut her eyes. The only wolf that could reach that high would be a giant twice the size of Papa’s prize stallion.

In daylight, she could see where the forest ended. The village lay twenty minutes’ walk away, though at night it had seemed impossibly farther. Ekaterina climbed very carefully down from the tree. Her limbs ached from running and climbing, and she didn’t trust them to hold her up.

She wished very much for a slice of wheaten bread and a glass of milk, and for Agafya to plait her hair, which was tangled and wrapped around twigs and leaves and bits of bark from her wild pursuit of the Firebird.

Sunlight filtered through the dark, crowded trees and birds sang high above her. Soon she would be home in front of the fire with a mug of kvass. She walked faster.

A masculine voice called, “Ekaterina!” It was Nikolai. Her family must have raised a search party. She thought again how bedraggled she must look.

She picked leaves and twigs out of her hair and twisted it into a rough braid. Then she called, “Here! I’m here!”

Her heart swelled when her rescuer—never mind that she no longer needed rescue—plunged out from between the trees. At the sight of Nikolai’s handsome face and the way his eyes fixed on her, she felt stirrings lower down. She blushed and envied how magnificent he looked in his gray-embroidered overcoat and waistcoat. His breeches were immaculate, and his stockings didn’t have a single snag. In comparison, she looked a bedraggled wretch.

“Ekaterina, I’m so glad to have found you.”

She would have protested his familiarity, but he seized her and pulled her to his chest. She pushed at him, and he loosened his embrace just enough to kiss her.

It was—interesting. She’d often wondered what it would be like to be kissed. His lips were firm and dry. His scratchy face rubbed against hers, and she was fleetingly reminded of her baba, a wrinkled apple of a woman with bristles sticking out this way and that. It ran in the family; Ekaterina had to pluck downy hairs from her own cheeks and upper lip every few days. Then Nikolai tightened his grip. The faint scent of sweat and leather rose up around Ekaterina, and his strong arms held her firmly. For a moment, she could think of nothing else.

He released her with a smug, masculine grin. “Why did you run off into the forest?” he scolded. “You must not do such things once we are married.”

“I was hunting the Firebird. But—married?”

“I spoke with your papa last night about the benefits to our families of joining together, and he did not tell me no.”

She lifted her chin, remembering Agafya’s warning. Nikolai was fine-looking, she admitted, and he had paid close attention to her at the feast, but he was no great conversationalist. He had seemed disturbed when she tried to discuss philosophy or the history she and her brothers had learned.

“Papa would never betroth me without my consent!” she flashed, angry at his presumption. “He’s told me many times that I am too young to think about marrying. I am sure he only said he’d think on it, and that because he did not wish to spoil the evening. Only last week, he assured me that I need not think of marrying for some time. As for benefits to our families, I see only the ones to yours.”

His eyes darkened. “Then you will have to persuade him,” he said.

Ekaterina was suddenly very conscious that they were still too deep in Chyorniy Forest for anyone to hear her if she screamed. She longed for Agafya, who had been there from her earliest childhood to ensure her virtue remained uncompromised.

Nikolai stepped forward.

She stepped back.

He lunged for her.

She turned to run, but her exhausted legs betrayed her. She stumbled and fell. He was on her in an instant.

“My father and brothers will kill you!” she spat.

“And who would have you then? No, a marriage will be in everyone’s best interest.”

She wriggled under him as he held her down and began to push her skirts up her legs. Desperate, she craned her neck—and saw a branch as thick as her arm that had fallen almost within reach. She scrabbled through the forest loam to grab it. As soon as she had the branch firmly in hand, she brought it whistling up at him, in a blow that would have split his skull if he hadn’t recoiled and jumped off her in the very same instant.

“What witchcraft is this?” he demanded, staring at her bare legs and backing away. “You are a leshy, trying to trick me.” He looked around wildly, as if he expected other spirits to coalesce from the forest’s shadows and attack.

Ekaterina hurt. Tomorrow, she would have deep purple-black bruises where he’d gripped her. The remembered joy of flirting on her birthday died like a rabbit crushed between a wolf’s jaws.

She braced the branch against the ground and pushed herself to her feet, swaying. Tightening her grasp on the branch, she took a step forward. Her throat was tight and her eyes stung, but a hot fire rose in her.

Nikolai turned and ran.

She threw the branch at him. It struck the back of his knees and knocked him down. Tree bark scraped his face as he fell. Blood seeped through his fingers where he pressed his hand to his cheek, but he picked himself up and fled.

Ekaterina circled around the village, keeping off the paths and sticking to the fields and trees. At the moment, wolves seemed safer than men.

When she saw her home, she ran toward it, despite her aching legs. She stumbled as she ran, but she could not stop herself. The guard dogs heard her first and bounded out, barking their welcome. Ekaterina collapsed to her knees and wrapped her arms around their necks, burying her face in Zaychik’s ruff while Belka stood guard.

Her mama and her brothers Vasily and Oleg tumbled out of the house. When Ekaterina’s mama saw her, she let out an inarticulate cry, hiked up her skirts, and ran to her. She pulled Ekaterina into a tight embrace as Vasily and Oleg stood awkwardly nearby.

Ekaterina had barely managed to choke out her story about the Firebird and becoming lost in Chyorniy Forest before she glanced over her mama’s shoulder and saw Misha, the brother just a year and a half older than she, running up from the village.

As soon as he was within earshot, he began talking. “Nikolai Semyonevich Egorov just stumbled into the village babbling of demons in the forest. He’s not the kind to be frightened into thinking the tree branches are reaching for him, but he said—” Misha stumbled to a halt and stopped speaking when Vasily and Oleg drew apart to reveal Ekaterina behind them.

Voice trembling, Ekaterina asked, “What did he say?”

The very air seemed to hold its breath.

“He said—he said that witchcraft had turned you into a man.”

“What? That, that peasant! He assaulted my honor.” Her mama went very still. “He found me in the forest and said we would be married. When I said no, he—he sought to press his attentions.”

“That worthless swine!” bellowed Vasily. “Come, brothers, let us go punish him for his temerity!”

Their mama put her palm flat against Vasily’s chest. “Wait. Ekaterina, before anything else is said or done, there is something your papa must tell you.” She paused. “And your older brothers, too. Oleg, run and find your papa and brothers.”

Ekaterina’s mama and papa gathered them all into the parlor: Oleg, Vasily, Aleksandr, Evgeny, Luka, Misha, and Ekaterina.

“Daughter—” her papa began, then stopped. “Ekat—” He cleared his throat. “Child. This whole mess began in the time of your great-great-grandpapa Leonti, during the reign of Mikhail I Fyodorovich Romanov. Our family was not so wealthy when he was born, but he was the seventh son of a seventh son, and that has always meant something special for us. In such times, the orchards flourish, and what we distill has a unique fire that makes each bottle sought-after. Our family prospers.

“Your great-great-grandpapa had a rival, Rostislav Fyodorovich Egorov.” At Ekaterina’s gasp of surprise, he nodded. “Yes, Nikolai Semyonevich Egorov is his great-great-grandson. The Egorovs have held a grudge against us for a very long time.”

“Then why did you invite Nikolai to my birthday feast?” Ekaterina burst out.

“Making a wolf pup believe it is a dog is one way to keep its fangs from your throat. At least for a while.”

Ekaterina frowned at that, but let her papa continue his story.

“As I was saying, they have always held a grudge against us. Vodka and brandy alike, people seek ours over theirs. In your great-great-grandpapa’s time, Rostislav went to a ved’ma living in Chyorniy Forest and paid her to put a curse on our family.

“Now, it happened that your great-great-grandpapa Leonti was a kind man, which is fortunate for all of us. One day, he was hunting in the forest with his dogs when he saw an old woman gathering firewood. ‘Wait, old mother,’ he said. ‘Let me do that for you.’ As you have no doubt guessed by now, the old woman was one and the same as the witch who cursed our family. Because he had helped her, she warned him of the curse, though she could not lift it.”

“What was it?” burst out Evgeny, Ekaterina’s second-youngest brother. “We are not cursed.”

“Not until now.”

The room fell into a silence sharp as winter’s first bite.

“This is what the ved’ma told your great-great-grandpapa: ‘In your family,’ she said, ‘the seventh son of a seventh son has always distilled an exceptional vintage. The curse that Rostislav had me put on you changed that. The next time there is a seventh son of a seventh son, what your family produces will be exceptionally awful. Instead of smooth fire, your vodka will be so terrible that not even the lowest beggar will drink it, and your family fortunes will be ruined.’”

“Over the generations, our family switched from making vodka to brandy. We prospered. When your grandpapa warned me of the curse, I laughed. Surely such a thing could never affect us in these modern times.”

Ekaterina’s papa looked at her. “I was at the distillery when you were born. When the next taste of brandy I had was rank and bitter, I knew the family story was not just a story.”

“I don’t understand,” Ekaterina said, though a numb, floating feeling was beginning to spread through her limbs. “There is no seventh son.”

Her papa and mama exchanged looks.

“We were going to name you Ivan,” her mama said softly.

“Oh!” Ekaterina staggered backward and placed her hand over the sudden pain in her stomach. Her back hit the wall and she sagged against it. Her brothers stared at her with stunned-ox expressions. What they saw on her face, she could not imagine. She slid down the wall and sat in a crumpled heap on the floor.

“So we named you Ekaterina,” her mama continued. “Instead of a seventh son, we raised a daughter. And all these years, with the help of your maid Agafya, we have kept the secret.”

“I knew I’d have to tell you one day.” Her papa sighed. “I thought it would be when you asked why we had not arranged your marriage. But now our secret has been revealed.”

After a blizzard of silence, Aleksandr asked, “If Ekaterina is—not our sister anymore, does that mean the curse will fall on us?”

Hearing “not our sister” opened a dull ache in Ekaterina’s heart. She let the numbness spread as she waited for an answer.

“If so, we will know soon enough. One can plan, but God puts everything in its place,” her papa said.

“Nikolai said that Ekaterina was a witch, or had been replaced by a forest spirit.” Misha looked at her with worried eyes.

Her mama put a hand to her heart. “Who was he talking to? Will they come here and demand to see Ekaterina?”

“Egorovs.” Her papa spat on the ground. “Always trouble for our family.”

Ekaterina shakily pushed herself up. “Let me go to the distillery while this is figured out. It is far enough away that trouble should not follow me.”

“Yes.” Her papa eyed her. “Pretending to be a girl will do no good now. You can be as you were meant to be, though we will need to introduce you as a cousin. The distillery is perfect—you can practice being a boy there.”

Ekaterina felt as if a pit had opened under her feet.

When Ekaterina set out with her papa, Vasily gruffly told her to lower her voice to sound more masculine. Oleg said that being a growing boy, she should eat all she wanted. Aleksandr loaned her half his wardrobe. Evgeny joked that Ekaterina was the best-looking of all the brothers, and understood women besides, so the girls had better look out. Luka said he’d keep watch for the Firebird and send word immediately should he spot it. Misha just hugged her goodbye.

At the distillery, Ekaterina’s papa said, “This is our cousin Ivan, who is interested in learning brandy making. Treat him as you would one of my sons.”

The workers bowed. Ekaterina bowed in return. That, at least, was the same for a man or woman. Wearing only breeches and waistcoat left her feeling naked under the men’s gaze, and the startling lightness of her short-cropped hair left her dizzy—and, when she was outside, cold.

The curse had not fallen yet; the brandy being made was neither extraordinarily good nor extraordinarily awful. “Perhaps the curse is still confused,” her papa said. “Nikolai is raising questions about your absence. We must wait.”

She waited. She missed home. She missed her brothers. Though men’s garb didn’t require assistance to put on, she missed the ritual of preparing for the day with Agafya by her side. She missed sitting in the kitchen and gossiping with Cook while learning her recipes. She missed evenings spent sitting beside the fire and spinning, or embroidering an ornate shawl for feast days.

The men expected her to join them in drinking brandy or vodka in the evening “to keep the wolves away.” She half-wished that she had let the wolves eat her instead.

Then she would not have to stride around half-naked and wholly not herself, being introduced to people under a fake name. She would not have to pretend she knew the ways of someone who had grown up a man. Her papa kept saying it was what she was meant to be, but it did not feel that way. It didn’t seem like it would get easier any time soon.

It all came to a boil one evening when her papa had a guest over for dinner.

“It is soon to think of, perhaps,” her papa’s friend said to her, “but I have an unbetrothed daughter of about your age, young and strong and loyal. She is skilled at spinning and embroidery, well-versed in household management, and even knows something of distilling spirits. She is a Godly girl, virtuous and happy in the place decreed for her in this world.”

Disorientation swirled through Ekaterina. Bile rose in her throat and she blindly stumbled to the door. She pushed it open and sucked in a deep breath of cold air.

“Ivan!” her papa called from the table. “Are you well?”

Ekaterina couldn’t take it anymore. She could not go back, where the overseer would greet her as ‘Ivan’ and clap her on the back, where her papa’s friend and others like him would speak of her being husband to his daughter as if it were the most ordinary thing in the world.

Her feet fell one in front of the other, her breath rasped in and out of her lungs, the wind whipped her cheeks, and she realized that she was running. Ekaterina was very good at running.

She ran past the distillery. She ran over the frozen creek and into the distillery’s apple orchard. Panting, she stopped in the middle of the trees, unsure where to go next. She collapsed on the ground, pulled her knees up, and rested her chin on them. She wished for a skirt to bury her face in.

Past the tree trunks, she saw gray stone and the swirling blue and gold onion domes of the church. People streamed out the doors as they left the evening service. Now that vechernya was done, she’d have the church to herself. She pushed herself up and stumbled through the orchard and down to the road.

Inside the church, she paused for a moment to cross herself and let her eyes adjust to the dimness. Banks of candles flickered. Gold-painted icons watched her with wise and mournful eyes. She venerated the icons and then lit a candle, sending up a prayer that she might know who and what she was meant to be. In the turmoil of her heart, she prayed for a long time, as the sky darkened.

When she was all prayed out, she stared numbly at the candles. Their flickering flame mesmerized her. The curve of them reminded her of the Firebird’s plumage. “It knows what it is—and its fruit is more delicious for it,” she heard the Firebird say.

She knew what she was not. She was not Ivan. Being a boy felt all wrong. She doubted she’d feel differently even if she’d been raised as a male.

She lit a candle in gratitude and left the church. Once she was among the apple trees, she flung her arms wide, tilted her head back, and shouted, “I am Ekaterina Davidovna Barteneva!”

The stars above flared brightly. One grew larger and shot down toward her. For a heartbeat, she feared she’d misunderstood God’s sign to her, and he was going to strike her down for her impudence. Then the star dipped and curved, and she saw it was the Firebird. Over the orchard the Firebird flew, dazzlingly bright, casting its shadow over the trees and onto Ekaterina, who stood openmouthed below.

A few shriveled apples remained in the distillery’s orchard, the ones so bird-pecked, worm-riddled, and difficult to reach that they had been left as not worth the effort in a prosperous harvest year. Now they glowed. The snow melted off them. Their wrinkles plumped out, their scars filled in, and their dark red skins shifted to tawny gold. The aroma of ripe apples filled the air and lingered even after the Firebird was gone.

Ekaterina plucked one of the apples and hefted it in her hand. Its flesh was firm, and its skin gleamed golden in the moonlight. She brought it to her nose. It smelled of apples and honey and long summer days. She hesitated and then took a huge bite out of it. The apple crunched under her teeth, and its flavor rolled over her tongue.

She was transported. Sweet and strong and complex, the flavor was beyond anything she’d ever experienced. She closed her eyes as the apple fell from her hand. The taste was all that she could think of. She did not know where she was, or even who she was. Then she swallowed, and the flavor faded slowly from her mouth, like memories of a heaven glimpsed.

Once she was herself again, Ekaterina ran through the out-of-season orchard and into the house. Their guest was long gone, and her papa sat on the bench beside the dining room table, his head in his hands. His dinner had cooled on the table.

“Papa, it’s me, Ekaterina,” she said, not bothering to deepen her voice.

He sat straight. “Ivan,” he corrected.

“No. Ekaterina. And,” she broke into a radiant smile, “the Firebird came again! He flew above me. The shadow from his wing fell over me and the orchard.” She sank to her knee beside him and took his hand. “All will be well. The curse has been broken.”

She pulled her papa out of the house, across the snow-covered ground, to the brandy distillery. He heaved the bar from the door, rushed through, and seized the tasting cup. His fingers trembled. He filled it under the spigot of the collection chamber, brought it to his lips, and swallowed. A beatific smile spread across his face.

He held the cup to Ekaterina. “Taste.”

The sip of apple brandy burned down her throat like fire from heaven. It had a primal edge that aging would smooth out, but it still tasted finer than anything her family had made in generations.

“Let’s go home, Papa. We have wonderful news.”

“Yes, but in a couple of days,” he said. “Our guest told me that Nikolai is deeply in debt, far beyond what he can recover from. He has been borrowing on his expectations and promising his creditors that you two were all but betrothed and that your dowry would be handsome. A word in the ears of his creditors, and he will soon flee far enough away that he won’t be able to cause any more mischief.”

When Ekaterina and her papa eventually returned home, Ekaterina’s absence and short hair was explained away by saying that she had been secluded because of a feverish sickness. To any who asked, Ekaterina said she was grateful that the fever had passed and her mind was clear again.

In the fullness of time, Ekaterina married a slim and beardless young man whose hair was the same golden-red as the apples in her orchards. The gossips who said Ekaterina was an “unnatural” woman grumbled their way to silence. Her husband was often away on business, but he always returned when the apples were ripe and golden. He seemed content to let his wife run her ancestral distillery along with her brothers.

During Ekaterina’s lifetime, all agreed that the brandy her family made was the best in all of Russia, fit to serve to the Tsar himself. And long after the reign of the tsars ended, the extraordinary virtue of Ekaterina’s apples endured.

“Ekaterina and the Firebird” copyright © 2013 by Abra Staffin-Wiebe

Art copyright © 2013 by Anna & Elena Balbusso